by

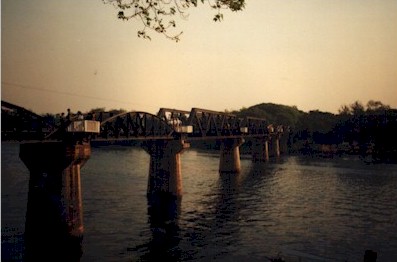

When people come to Thailand, one of the first things they want to visit is The Bridge on the River Kwai. Made famous by the 1957 film starring Alec Guinness, William Holden and Jack Hawkins, the bridge is one of the biggest tourist attractions in Thailand today.

The rebuilt Bridge over the River Kwai

Located in Kanchanaburi, it's 120 km west and about two hours drive from Bangkok. The town was founded by King Rama I against a possible invasion by Burmese soldiers through Three Pagodas Pass.

Kanchanaburi is a pleasant town with beautiful scenery, nice people and numerous picturesque Buddhist temples. Many people stay in guest houses which are located right on the river. It is a great place to escape from the hustle and bustle of busy Bangkok life.

From rich tourists traveling on expensive package tours to backpackers traveling thru on the cheapest form of public transport, hundreds of people make their way to Kanchanaburi everyday to catch a glimpse of the famous bridge.

The movie won three major Oscars as Guinness won for best actor, David Lean for best director and the movie itself for best picture. The screenplay was adapted from a novel by Pierre Boulle and ironically enough, as so many movies on Vietnam are made in Thailand, the film was shot in Sri Lanka and England.

The film itself was a work of fiction, but over time people have come to think that the story was based on true characters. The conditions that Boulle describes were very real though as he had been a prisoner-of-war himself.

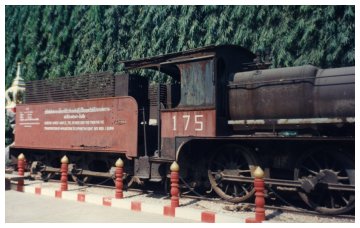

During World War II, the Japanese used this train for the transportation of ammunition

to expand the fight into Burma and India

There are two museums in Kanchanaburi, the JEATH Museum and the World War II Museum. The JEATH Museum was built in 1977 by the chief abbot of Wat Chaichumpol. Its bamboo structure resembles the huts the POW's were forced to live in during their internment. JEATH is an acronym for the soldiers of Japan, England, Australia, Thailand and Holland, all of whom helped build the infamous Death Railway.

The World War II Museum, located at the site of the old bridge, was opened on 5 December 1988 by Boonyiam Chansiri and her family. Her father died fighting the Japanese when she was only eleven years old.

The Death Railway stretched for 415 km from Thanbyuzayat in Burma to Nong Pladuk in Bangpong District in Ratchaburi province in Thailand. 304 km of the railway was located in Thailand and the remaining 111 km in Burma.

More than 16,000 prisoners died during the construction of the railway or about thirty-eight prisoners for every km of railway built. The prisoners died because of sickness, malnutrition and exhaustion. There was very little or no medical treatment available and many prisoners suffered horribly before they died.

The prisoner's diet consisted of rice and salted vegetables served twice a day. Sometimes they were forced to work up to sixteen hours a day under atrocious conditions. Many prisoners were tortured for the smallest offenses. The Japanese commander's motto was "if you work hard you will be treated well, but if you do not work hard you will be punished."

Punishments included savage beatings, being made to kneel on sharp sticks while holding a boulder for one to three hours at a time and being tied to a tree with barbed wire and left there for two to three days without any food or water.

Boulle's book probably best describes the attitude of the Japanese officers. "From the very start they acted like savage chain-gang wardens and were liable to turn at a moment's notice into sadistic executioners."

Japan signed the 1929 Geneva Convention relative to the treatment of POW's, but it did not ratify it. Many people cannot understand how the Japanese could have treated their prisoners so badly and many survivors of the Death Railway can still not forgive their Japanese captors to this day.

It is ironic that after the war many of the Japanese soldiers who were interviewed said that although they could not understand how easily the Allies surrendered at first, they were amazed at the tenacity and determination they showed in building the bridge and the Death Railway. "I was overwhelmed by their tenacious spirit," said Takashi Nagase, an English interpreter for the Japanese military police.

Part of the reason for the Japanese behavior may lay in their attitude towards surrender. Most of them would rather die or commit suicide than surrender. Their opinion of the Allied soldiers was very low because they couldn't understand how the Allies could give up so easily and not be consumed by guilt because of it.

The Japanese were determined to build a railway to create a new route from Rangoon and the Bay of Bengal through Bangkok to Singapore. They thought that by relying on sea routes only, they would be vulnerable to Allied attacks, so they needed another method of transportation. They also had their sights set on the British Empire in India.

The Japanese had struck a deal with the Thai PM Field Marshal P Pibulsongkram on 21 December 1941 to occupy Thailand as long as they didn't interfere in the country's internal affairs.

On 8 August 1942, the Prime Minister signed an agreement with the Japanese representative General Sheji Poriya to build the railway. The Japanese hoped that the single meter gauge railway would be able to transport 3000 tons of supplies and strategic materials a day.

The Death Railway branched off from the existing southern railway and headed towards Kanchanaburi. The first fifty-five km from Nong Pladuk to Kanchanaburi were easy to construct because of the flat terrain. The rest of the way was hell though and that is how it earned its nickname.

When the first survey on the railway was completed it was estimated that it would take five years to build. The principal engineer was S.O. No. Construction began in October of 1942 and it was finished in August of 1943. The railway was put into use on 25 October 1943. The two tracks, one starting from Thanbyuzayat in Burma and the other from Nong Pladuk met at Nieke just south of Three Pagodas Pass.

After the railway was completed, 30,000 prisoners were kept in six camps along the railway to maintain it. These camps were close to the bridge and other strategic positions so they became vulnerable to Allied attacks and many prisoners were killed in bombing raids.

Nowadays, as you wander around the finely kept grounds of the cemeteries holding the prisoners remains you can't help but notice how young some of the prisoners were when they died. Many were in their late teens and early twenties and it was probably their first time away from home. What a tragic way for so many young men to die. The Japanese were so concerned with getting the railway built quickly that they gave little or no concern to the welfare of their prisoners. They thought it was a fabulous piece of engineering that the railway was completed so fast.

In his book, No Time For Geishas, Geoffrey Adams says that "Those POW who never went above the bridge at Tamarkan could count themselves fortunate indeed, for the Japanese in the base areas never displayed the same cruelty and callousness as did those further up-country in the jungle camps. Conditions there, especially during the 1943 monsoon, were unimaginable by those who did not suffer them."

By early 1943 disease, starvation and overwork had so depleted the prisoner's work force that the Japanese were forced to hire 200,000 Asian coolies to help finish the railway. Many of these impressed laborers, who were predominately Chinese, Malay, Tamil and Burmese met with fates worse than the prisoners. It is thought that at least 80,000 of these laborers met unfortunate and untimely deaths but the number could even be as high as 150,000 as no records of them were kept.

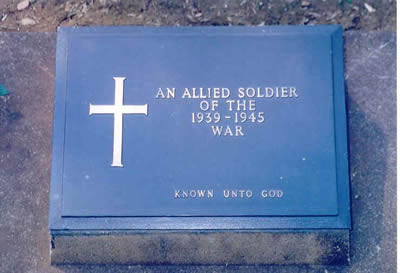

The remains of about 12,000 prisoners lie in three cemeteries at Kanchanaburi, Chungkai (which is across the river and about two km down the road from Kanchanaburi) and Thanbyuzayat in Burma.

The bridge you see standing today is in fact not the bridge the POW's built. You can, however, see a section of the old wooden bridge. As mentioned, it's located in the World War II Museum, which is right beside the modern bridge.

Visiting Kanchanaburi today, it is hard to imagine the suffering the prisoners went through in order to build the Death Railway. 61,700 prisoners were brought in to build the railroad. They came mostly from camps in Singapore, Malaysia and Indonesia, and they had been captured in earlier battles with the Japanese.

The railway was built with a few pulleys, derricks, cement mixers, a lot of hard labor and a tremendous amount of ingenuity. It took a tremendous toll on its builders.

| Workers on the Death Railway | Total Deaths |

|

| Asian Laborers | 200,000 | +/- 80,000 |

| British POW's | 30,000 | 6,540 |

| Dutch POW's | 18,000 | 2,830 |

| Australian POW's | 13,000 | 2,710 |

| American POW's | 700 | +/- 356 |

| Korean & Japanese soldiers | 15,000 | 1,000 |

Approximately one in five prisoners died during the construction of the railway. It is estimated that every railway sleeping car cost the life of one prisoner.

Every year in the first week of December there is a sound and light show at the bridge commemorating the Allied bombing of the Death Railway in 1945. The railway today only exists as far as Nam Tok at the 130 km point.

The Japanese should have never pushed their prisoners the way they did and yet so many prisoners performed Herculean tasks in the face of great odds to complete the railway as quickly as possible. The Death Railway is both a testament to man's capacity for evil and to man's unfailing tenacity and bravery.

****************************************************************