HELPING THE WORLD'S STREET KIDSby

Gotta admit: I was skeptical at first. When I saw Peter Dalglish and his entourage prance through the grounds of Bangkok's Siam Intercontinental Hotel, during a Canada Day celebration, shouting, "We're here, we're here," I thought "Oh great, a bunch of rich preppies here to save the world."

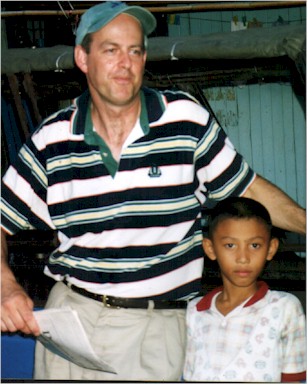

Peter Dalglish and FriendWhat were these kids from Upper Canada College going to teach street kids from Bangkok's toughest slums: survival tools? But you see, I had it all wrong, it wasn't what they could teach the kids, it was what the kids could teach them.

As Peter says his disciples "can't help it if they were born into a wealthy family." But it is precisely because of that affluence that these kids have the potential to do so much good. "Upper Canada has been training kids for Bay Street for years," he says, "but now it's time to train them for something else."

Peter cites Philip Exeter Academy in New Hampshire as an example of a prep school that started recruiting talented kids from the ghetto and achieved a far richer and diverse educational system because of it.

Spend any time with Dalglish, and you can't help but like him. He's kind of contagious, a sort of positive energy wave that just flows over you and oozes through your pores. Maybe the cynic in all of us wants to dismiss him: I mean how can he possibly save the world. But you see he's not trying to, he's just trying to make it a better place for a group of kids that have been dealt a pretty crappy lot in life.

So where did this philanthropic streak come from?

After articling at Dalhousie Law School, Peter was poised to make a lot of money, drive a BMW and have all the other nice legal trappings but something happened: the Ethiopian famine came along.

Peter decided to organize and accompany an airlift of food and medical supplies to Africa. He spent the last two weeks of 1984 in a refugee camp with 25,000 children in the Ogaden refugee camp on the Somali/Ethiopian border.

He then decided that perhaps the world didn't need another corporate lawyer, perhaps there was some way he could make himself useful by helping needy children.

In the new year, Peter went back to Canada where he was clerking with Stewart, MacKeen and Covert, one of the largest law firms in Eastern Canada. But three days after being called to the bar on 15 May 95, he set out to work in the Sudan monitoring food distribution in the most remote area of the country: the border region between western Sudan and Chad.

"Emergency operations in a time of famine or war are a lot like the military: if you are any good at all and you are young and healthy, you get promoted quickly; often you are promoted far beyond your level of professional training. Within six months of arriving, I was coordinating emergency operations for UNICEF for the entire country.

"I was also very involved in cross-border operations in southern Sudan working with the rebel authority. It was difficult and dangerous work but it was important because tens of thousands of people were on the verge of starving to death.

Peter thrived and loved his work. "Emergency work at its best requires resourcefulness, which is a skill which is not so important in the West. In developed countries, when you run out of something, you just run to the nearest 7-11, but in the desert there is no 7-11. So when you're diesel land cruiser breaks down in the middle of nowhere, you've got to know how to fix it. If you have twenty tons of food and a camp of 5,000 people, you've got to find some way of distributing it equitably without causing a riot or the local mafia taking control and exercising their power. It requires equal amounts of resourcefulness, ingenuity and moxie: the ability to do deals, and innovate quickly. It's not the type of work a committee can do.

So what's he doing in Bangkok? Dalglish estimates there are 8,000 boys and girls in Bangkok's jails. The vast majority have not committed, or even been charged, with a criminal offense, but they are caught up in the system. They have been rounded up and stuck in jail because there is nowhere else to put them.

One of Peter's tasks is to aid Father Joe Maier of the Human Development Center set-up Bangkok's first Legal Aid Clinic to help these kids. The plan is to work with the Thai authorities, the Department of Social Welfare and the police and prosecutors to look for alternatives besides putting street kids in jail. "We've learned in the West, that one of the best ways of predicting whether someone will commit a criminal offense as an adult is to ask one question: `Have they been incarcerated?'

"If you want to increase the numbers of criminals in your society, put kids in jail when they are young. They will learn all the tricks of the trade, fall in with the worst elements of society and meet all kinds of corrupt policemen. The single best thing we can do for these children, apart from putting them in schools, is to keep them out of jail - keep them out of the criminal justice system. We talk in the West about `diversion programs' - diverting children and youth from the formal criminal justice system by putting them in other programs, that's an important theme of his Legal Aid Clinic. Once you become part of the criminal justice system, there is a process that kicks in, you are drawn into it and your chances of getting out of it are pretty minimal.

Back to how Peter got started working with street kids. In February of 1986, after he had been reassigned to Khartoum, Peter caught an eleven-year-old breaking into his land cruiser. He was pretty angry and about to turn him into the authorities, but then he realized that if the kid could break into his car with a bent nail, he must have a good set of hands. So Peter preceded to set-up the first Technical School for Street Kids in Khartoum. He had met Bob Geldoff, so he wrote him a five page proposal and Geldoff funded the project: he wrote Peter a cheque for US$50,000, and the project opened 13 May 86.

Within a few months, eighty of the city's best pickpockets and car thieves were turned into carpenters, welders and mechanics. When Peter talked to the kids, he found out that they left school because they needed to immediately find some way of supporting themselves. So he had to find some skill that these kids possessed which could make them some money in a way that was legal.

Peter's next project? Well, as the infrastructure of Khartoum was horrible, the phones didn't work (Peter claims that he completed three phone calls in six months) and the mail system didn't either, but people needed a way to get messages around, so he decided to establish a guaranteed same day bicycle courier service. This was inspired by his Boy Scout's experience where he learned Lord Baden Powell had effectively used kids as messengers at the Battle of Mafeking during the Boer War. He realized the street kids of Khartoum knew the streets of the nation's capital better than anyone. Why? Because they had broken into all the buildings. So why not take these same kids, put them on bikes give them uniforms and have them delivery mail to the very offices they used to break into? This time they would walk through the front door instead of climbing in the back window. And people loved it because in a city where nothing worked, the kids delivered the messages on time.

"You know the funny thing about street kids," he says, "they like money, they are little entrepreneurs. They take twenty-five cents in the morning and turn it into two dollars at the end of the day - they have to be resourceful, it's called survival. What they lack is access to capital and human resources - they can't do things like sign a lease. But we built on the resilience of these kids and their ingenuity. We provided them with a little infrastructure and support by renting them an office and providing them with bikes and that's how in September of 1986 SKI Courier came to be."

In August of 1987, Peter returned to Toronto, to set-up similar projects around the world and a month later he incorporated Street Kids International. SKI's logo is a flying kid - this represents freedom and the children's ability to persevere and to rise above the misery and suffering that goes on in shantytowns.

The volunteers Peter takes on his jaunts around the world are hand-picked, he wouldn't just let any Upper Canada kid tag along, but the process itself is self-selective. "How many sixteen-year holds want to give up lying on the dock in Muskoka to come and live in a shantytown and work with urchins for a few weeks?," he asks.

Last fall, Peter was hired by Upper Canada College to run a very ambitious program for inner-city youth in Toronto, called the Horizon Project. It's similar to programs that very progressive US schools have been using for years.

He has seventy-five kids from UCC volunteering for the project, and it amazes him how they crave the experience of working with inner-city kids.

"We all have a biological need to needed," he continues, "We need to know that we can make a difference. The problems with kids of affluence is they rarely have the opportunity to give anything of themselves. So I try and act as a catalyst, and show them how they can make a difference."

It became obvious to Peter in 1987 that AIDS was going to be a big issue for people in the developing world. "Remember, back then AIDS was seen primarily as a disease of rich gays in North America and Europe. People hadn't yet figured out that it would become a disease of the urban poor. But when you talked with community health workers, they would tell you that one of the most common ailments they were treating, after cuts and bruises and stomach aches, was sexually transmitted diseases. So you didn't have to be Louis Pasteur to figure out that soon these kids would be exposed to HIV because they were sexually active at a very early age.

Peter needed to find a way to teach street children about HIV. Fortunately in 1987, while showing a Tom and Jerry film to a bunch of street kids in Khartoum, he had been amazed that their reaction to the film had been immediate and electric. The kids were mesmerized by the images of mice being chased by cats, so Peter had a brainstorm: create a cartoon to teach kids about HIV, and he went back to Canada armed with this idea.

He eventually went to the National Film Board of Canada where he teamed up with producer Michael Scott who recruited Derrick Lamb, a two-time Academy Award winner for animation and they in turn recruited a very famous Danish-Canadian animator named Kaj Pindel. With the filmmakers in place, Peter's task was the fundraising: he had to raise about CAN$200,000 to get the project started and in the end it cost CAN$1.7 million to make the first film. But within three years, they had done it: they created a twenty-two minute animated film. It's hand-drawn, hand-colored images created by professional animators.

From his Tom and Jerry experience, it was obvious to Peter that they had to create films that were entertaining, and not the regular boring health promotional type films. The original film on HIV was called Karate Kid, the second film, entitled Goldtooth, deals with substance abuse and the third, on helping kids set up small businesses, is still in production. They are the single largest products for street kids in the world. They have been translated into twenty-five languages, seen in over 100 countries and watched by hundreds of thousands of street children all over the world.

The films are still used and if anything they are gaining strength. They are used in Thailand by the Thai Red Cross (with a comic books as well). Peter says the films aren't the answer, but they are part of the answer. They spark discussion about HIV and sexual abuse. They are banned in two countries: Kenya and the Philippines (because of the condom message in the film).

So how does one take the Convention on the Rights of the Child and give it teeth? "Politicians love legislation, community workers generally don't," Peter says. "Laws can cause more problems than they solve, they are rarely the answer for complex social issues. Laws without political will mean nothing, in fact, they can be a step backwards because what laws do is they suggest to people that the problem has been solved. People think we don't have to worry about child labor because we have legislation combating it, but we've had legislation forbidding child labor since the first meeting of the ILO back in 1919. UNICEF calls it the Magna Carta for children, but if a street kid in Brazil tells a police officer that he has rights because of that constitution, and that he shouldn't be beaten or raped, the police officer will laugh and probably hit him harder.

"The Rights of the Child should be used as a catalyst to remind people that nine-year-holds shouldn't be in prison with twenty-five year holds. Kids that go in on a vagrancy charge are usually raped and that can become a death sentence.

Peter has definitely had an eventful forty-two years on Planet Earth so far, from working with the world's impoverished in deepest darkest Africa to working with some of the world's most fortunate in deepest darkest Forest Hill.

Having worked with Mother Teresa, he's fond of quoting one of her favorite sayings: "We can do no great things, we can only do small things with great love." Good maxim - we should all live by it.

Email - peterdalglish@hotmail.com

FINIS